Historic Renovations Hinge on Intricate Numbers Game

The following are excerpts from an article written by Melinda Waldrop that appeared in a print version of the Columbia Regional Business Report.

The following are excerpts from an article written by Melinda Waldrop that appeared in a print version of the Columbia Regional Business Report.

Feb. 25 FOCUS: Banking and Finance

Historic Renovations Hinge on Intricate Numbers Game

Chris Rogers needs only to look out his office window to find inspiration.

Rogers, an attorney with Columbia law firm Rogers Lewis, is also a member of a local limited liability company that scouts the Midlands and beyond for promising development projects, particularly ones that can benefit from federal and state historic tax credit incentives.

“There’s a building that I like over here on the other side of Assembly Street,” Rogers said from a 12th-floor conference room at his firm’s Bank of America downtown office building. While he doesn’t know if the white, three-story building that used to house a real estate brokerage would be eligible for tax credits, “I see it every day, and I’m like, ‘We could really do something with that building.’ ”

A turn to the north produces similar thoughts as Rogers’s gaze falls upon the former Stone Manufacturing building at 3452 N. Main St. “It’s just sitting there empty,” he said. “It’s a big, empty building that is sort of a blight on the surrounding community. If you can take that building and put something nice in it and put it back to use, it just turns the whole community around.”

Rogers knows of what he speaks. Rogers Lewis Jackson Mann & Quinn LLC has been behind some of Columbia’s most noteworthy transformations involving historic tax credits, including Hotel Trundle, a boutique hotel born out of three empty properties at the corner of Taylor and Sumter streets that opened last April, and the Hunter-Gatherer, the second location of a popular downtown brewery that landed last January at the Curtiss-Wright Hangar adjacent to the Jim Hamilton-L.B. Owens Airport.

“A lot of what we do is bring the right people together,” Rogers said. “We look for things that nobody else is doing. We don’t try to compete with clients, but we do have a lot of developers who come to us and say, ‘I’d like to do this building. How can you help us make this happen? We understand there are credits.’ That’s the way it usually starts.”

….

“We start out with a financial model, a pro forma financial model,” Rogers said. “We look at the capital stack, which is sources and uses. Where’s the money going to come from and what’s it going to cost? That’s the first step. The second step is, once we get this built, what can we expect to receive in rents, and what are our costs going to be? What is the cash flow going to look like after we create this project?”

A hypothetical: Say a project eligible for state and federal historic credits, as well as the state abandoned building credit, has a $10 million budget of eligible cost.

“There’s a 20% federal historic tax credit,” Rogers said. “You can’t sell the tax credits, but (investors) invest in the project as a partner, and in exchange for that investment, they get the bulk of the tax credits and some minimal amount of cash flow from the project. That’s what developers need. A lot of them don’t have the cash and the tax liability to be able use those credit themselves and to put the cash up on the front end. So if we bring in, let’s say a bank, who can use the credits and has the cash to invest, it’s a good partnership. It puts the cash in the project to allow it to go forward, it’s a good investment for the bank or the investor, and it helps the developer get his deal done.”

While the tax credits help mitigate some of that cost, the process — which requires layers of IRS third-party investor compliance, among the plethora of paperwork — was not readily embraced by would-be financiers when rehabilitation projects first came into vogue, Rogers said.

“Ten years ago, nobody understood tax credits,” Rogers said. “You went to a bank and they looked at you like you were crazy. They were like, ‘Well, who’s paying for this? Who’s losing? Is this some kind of scam?’ It would take a lot of education. Most of the banks have been exposed to it now, and they understand it. The structuring of the transaction is more intense and more sophisticated, so it involves some more work on the front end, but when you’ve got that kind of money coming in as equity, it helps the bank. Obviously if there’s less debt and more equity, it makes the bank feel more secure.”

Related Posts

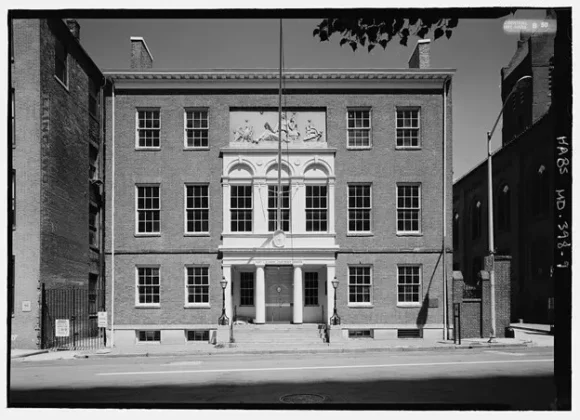

The Peale Wins 2024 Buildy Award

Mar 8, 2024

The Peale Center for Baltimore History and Architecture (The Peale) brings new life to the first purpose-built museum in the Americas, both architecturally and organizationally. The Peale’s National Historic Landmark building was […]

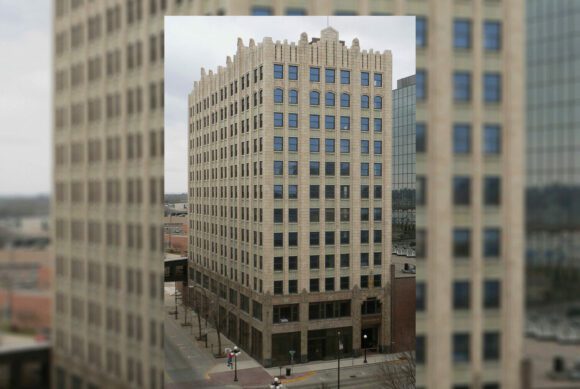

Historic Badgerow Building grand opening brings excitement to downtown Sioux City with new apartments

Aug 18, 2023

July 13th was the grand opening for apartments in the historic Badgerow Building. ”This is a beautiful and one of the most magnificent buildings in all of downtown and to […]

Monarch Private Capital and WEDI Partner to Support a New Home for West Side Bazaar

Jul 19, 2022

Buffalo’s West Side Bazaar, a program of the Westminster Economic Development Initiative (WEDI), secured Historic and New Markets Tax Credit equity from Monarch Private Capital with which to invest in […]